“I grew up in a colonial situation in Zimbabwe where we were discouraged from reading anything in our mother tongue,” says author and activist Elinor Sisulu. So the Puku Children’s Literature Foundation developed in response to ensure that books in a child’s first language are available.

Sisulu says the best marketing for a book is other people’s opinions, and thus the foundation’s website is a review hub and search engine for children’s books in South Africa’s 11 languages. On the site are a range of picture books, fables and tales, poetry, rhymes and riddles as well as educational books (fiction and nonfiction). Puku also stages a number of events such as the Puku Story Competition and the Story Festival, held annually in Grahamstown.

The inaugural event took place in September 2013 and, like Puku itself, continues to evolve, but always in response to the relative lack of availability of mother tongue children’s literature. Puku has its origins in the Book Development Foundation, which consists of various players in the book chain.

It enjoyed a partnership with the Centre for the Book, which co-ordinates book-related events nationally, until 2007. The Mail & Guardian spoke to Elinor Sisulu about Puku.

What is the genesis of the Puku Children’s Literature Foundation project?

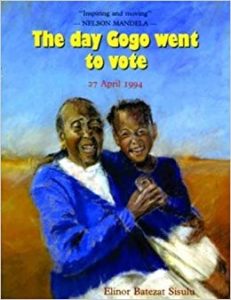

I had written a book called The day Gogo went to vote. It did so well in the United States. I saw how people review books there and their interest in children’s books. I noticed that the book didn’t get similar attention in South Africa.

That’s what interested me. Also, there are a lot of children’s books in indigenous languages but they are not sufficiently marketed, distributed and promoted. When a book goes to market in the US, all the different departments and the different libraries will review it.

The day Gogo went to vote made it on to the American Libraries Association’s 100 best books for the year it was published. It also made it on to the Smithsonian Institute’s 100 Best Books. Part of Puku’s main [mission] is to make sure that books are reviewed, especially African language books.

Why the focus on children’s literature?

In isiXhosa and isiZulu, there are classic works that exist, the works of [Samuel Edward Krune] Mqhayi and [James Ranisi] Jolobe, for instance. Not necessarily only for children, they are just great literary works. Speakers of those languages don’t know of those great works, but if you’re studying English, it’s very hard to escape Shakespeare. We try to make up for that disjuncture by using children’s literature. It promotes heritage, culture, language and history.

How has your annual story festival evolved since its beginnings in 2013?

The festival has grown, mostly through a Facebook page. People interact there in terms of storybooks for the language. There have been hundreds of schoolchildren who, for the past two years, have had access to the storytellers and writers that they otherwise would not have access to.

It coincides with International Mother Tongue Day in February. We also bring in people who are neglected. Iimbongi (poets), for example, are people who create in their language but are not recognised. We help them help others.

How do you ensure that books are used in the school system as children go through the various grades?

That is not a transparent or easy process to understand. And there is this attitude of commissioning a lot of work to suit the curriculum, instead of checking the literature available. So we are trying to establish an authoritative body of reviewed works and a network of people involved who are respected in their various linguistic communities. Interestingly enough, it is the Afrikaans reviewers who are having an impact because Afrikaans people look out for children’s books in their language, which is something I wish we could learn from them. We know the historical reasons, so we also need more investment put into our books.

Has this investment been forthcoming?

In some respects we have succeeded. We have Redisa [the Recycling and Development Initiative of South Africa] who recycle tyres. But because they are interested in educating people about recycling in their mother tongues, they have supported Puku.

We also get support from Thebe [Investment Corporation], which want to promote literature that will benefit communities. We are also seeking to drive investment into the digital space, where African languages are not prominent. We need to get work translated into African languages and get people to write in their own languages. The most challenging part of this work is getting funding in order to pay people to write in their own languages. There is a lot of continuous investment into English. The digital space is tricky because people talk about free content, but the producers of that content must get paid, so that’s the tension we experience.

Why not be directly involved in the selling of books?

When we were linked to Books Live, Puku would get a small commission. By definition, if you review a book and somebody buys it, you’re involved in the selling.

How has the market for children’s indigenous language literature grown?

There is Nal’ibali (the national, multilingual reading for-enjoyment campaign) and there’s the African Storybook Project (a digital project). There’s Biblionef (a book donation campaign), which promotes children’s books. I suspect that the Rhodes Must Fall movement has resulted in an increase in the demand for African culture and heritage.

We have been having people call us with an interest in expanding [this aspect] of literature. With the decolonising of the literary space, there are some who realise that you cannot even begin to have that until you deal with children’s literature.

What are your observations about how this conversation has been unfolding?

From Franschhoek last year, when Thando Mgqolozana raised the issue of decolonisation, [I can say that] if you talk about this and you don’t reference what people have been doing in children’s literature … then you are missing a key link.

I must mention Gcina Mhlophe. Gcina has done amazing work over the past 35 years and I don’t think she is sufficiently recognised for the volume of work she has done. She has written, she has recorded, she has talked to thousands and thousands of teachers. She runs a festival in Durban. At Puku, Gcina Mhlophe has been one of our main inspirations. If people had listened to Gcina and Sindiwe Magona and watched what they were and are doing, we would be much further in this decolonisation mission.

I was not there when this thing broke out but I was one of those who agreed with Zakes Mda’s criticism that we should be angry with ourselves. The people that should transform things are us and the people that we have voted for to put structures and institutions in place. For example, the National Arts Council has an important mandate.

If I was in a situation of power, I’d put much more money in it to fund community literature, storytelling and language projects. I’m told government has put R1-billion to build libraries, but if you ask them how much was put into books and content, I don’t even think it goes to nearly a fraction of that amount.

What does the near future hold for Puku books?

We want to get to a situation where we are not constrained by resources, and to become a tool where any parent or teacher who wants to find books in their own languages can. And then, to get the reviews.