Nsah Mala is a Cameroonian poet, writer and children’s author of 2 fantastic, illustrated books which have been well acclaimed for their unique angle and the colorful and beautiful pictures they contain. Muna Kalati had the opportunity to interview him to know more about his journey as an author, his experiences, challenges, and vision of the children’s book industry in Cameroon.

Muna Kalati [MK]: How was your encounter with books and your first reading experience?

Nsah Mala [NM]: I cannot trace my encounter with books and reading to any specific date or event apart from my first meeting with the English alphabet in CBC School Mbesa in the mid 1990s. And I also remember picking up books, including books in Hausa, from my father’s boxes and becoming friends with them while still in primary school.

MK: What were the first children’s books you read? Were they African? What did these reading practices teach you as a child?

I would say most of my first children’s books were primary school textbooks with illustrations, including the classical “Tales from the Grassland and the Forest.” So, yes they were African books. These practices nursed in me the love for both reading and writing literature.

MK: Could you give us an overview of your career? Why did you become interested in the world of children’s books? Is it a choice or the work of destiny?

NM: After reading Anne Tanyi-Tang‘s “Ewa and Other Plays” in Form Two in Government Secondary School (GSS) Mbessa, I wrote my first play called “Taku” during the holiday leading me to Form Three. By the time I finished Form Five, I had written four plays, all unpublished till date. In high school, I began writing poetry as well. My first poetry collection “Chaining Freedom” was published in 2012. Since then, I have published five poetry collections, including one in French, viz. “Bites of Insanity” (2015), “If You Must Fall Bush” (2016), “CONSTIMOCRAZY: Malafricanising Democracy” (2017), and “Les Pleurs du mal” (2019).

I have also co-edited three poetry anthologies, including a recent international bilingual (English and French) anthology on the Anglophone War in Cameroon entitled “Corpses of Unity – Cadavres de l’unité,” and contributed poems and stories to numerous magazines and anthologies across the globe, including “Redemption Song and Other Stories,” the Caine Prize Anthology 2018. I came into children’s writing both as a choice and the work of destiny, God’s hand, I should say. Specifically, I was invited by the dearth of children’s books from Africa and the near absence of black characters in children’s literature. Issues of diversity!

MK: What are the challenges that you have encountered? Was it easy to be published and it’s possible to live from the revenue of your books?

NM: Access to publishing channels is one of the most acute challenges all writers in Africa face. I’m no exception. And then there is also the dilemma of having books published and available in the West while they are difficult to purchase in Africa, where most target readers are found. It is possible but very rare to live off writing alone as a source of income. And I have not yet come close to such a juncture in my career. Indeed, it is very difficult. Very few writers, even in the West, ever succeed to live off only from writing.

MK: How do you promote your books and what has been their reception by the readers?

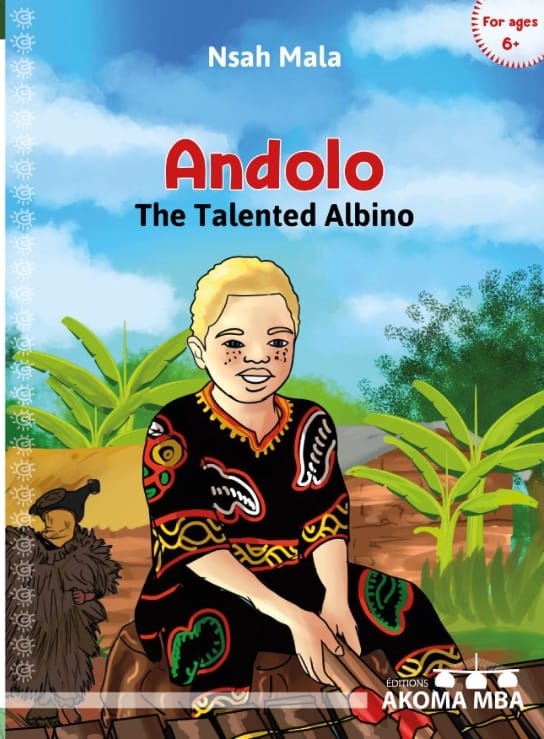

NM: I assist my publishers by promoting my books on my social media handles, especially Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn. And by jumping at opportunities for interviews like this one from you at Muna Kalati. So, thank you. My picture books, particularly “Andolo: the Talented Albino,” have been well received by children, parents, newspapers, book clubs, research institutions, and so on, from Cameroon through Nigeria and Kenya to the UK…

MK: How many children’s books have you published to date? Could you name them? Would you like Muna Kalati to review these books?

NM: So far, I have published two children’s picture books, each of them in English and French, namely:

- “Andolo: the Talented Albino” (Éditions Akoma Mba, 2020)

- “Andolo, l’albinos talentueux” (Éditions Akoma Mba, 2020)

- “Little Gabriel Starts to Read” (Spears Books, 2020)

- “Le petit Gabriel commence à lire” (Éditions Stellamaris, 2020)

I have translated one picture book from English called “Be a Coronavirus Fighter” into French as “Un Combattant du Coronavirus” (Yeehoo Press, 2020). And I am super excited about my picture book “What the Moon Cooks” which was acquired by POW! Kids Books (USA) in summer 2020 and will be published in 2021. The book deal was announced in Publishers Weekly. Of course, I would be very glad and grateful if Muna Kalati reviews my children’s books.

MK: Do you collaborate with other writers and illustrators of children books in Cameroon or in the diaspora? If yes, how.

NM: I am in connection with a number of Cameroonian and African authors and/or illustrators as well as those from Europe and America. Some of my collaborators include Akira Junior (Fakala Richard), Tifuh Awah, Alain Serge Dzotap, Tololwa Mollel, NJ Mvondo, Christian Epanya, and so forth. Yes, we collaborate behind the scenes. And I am sure time will also come for public collaborations.

MK: Are you conducting any action for the promotion of children and young adult literature in Cameroon or Africa?

NM:Yes, even before my first children’s book was ever published, I had been actively promoting the culture of reading among children in Africa in general and Cameroon in particular. For instance, I made live videos on Facebook to draw parents’ and children’s attention to free online children’s book sources in Africa such as Book Dash in South Africa and African Story Book where countless children’s stories can be downloaded or read online free of charge. Moreover, my doors are always open for collaborations in this domain, including interviews like this one, or TV appearances, workshops, etc.

MK: The children’s book industry is not well known in Cameroon and Africa, especially by parents. How do you explain this phenomenon?

NM: Children’s books are less known by an adult public which largely does not read adult books. So, it is a cause-effect scenario. Moreover, there are almost no political institutions in Cameroon, for example, which seriously engage with promoting and popularising the sector. You see?

MK: Yes, I see, very sad reality. So, how would you describe the culture of reading in Cameroon? Do you have ideas to make things better?

NM: As already pointed out, both adults and institutions are to blame for the dearth and timidity that we experience in the book and reading sector more generally. Take the case of Cameroon, how many serious public libraries do we have? Not to mention specialised children’s libraries.

We need well-furnished public libraries, especially municipal libraries, with functional outreach programmes. Of what use are books hoarded in a library? None. So, libraries should be able to lure people into reading the books they hold.

In addition, schools should encourage and reward reading for pleasure or self-edification among students instead of only reading books on prescribed educational booklists.

Finally, the civil society and social entrepreneurs should do more to preach and spread a culture of reading in Cameroon and elsewhere in Africa. For instance, they should organize book readings in different places or through mobile caravans, encourage the setting up of reading clubs in schools, carry out sensitization campaigns on the importance of reading, and so on. Let me use this opportunity to commend Éditions Akoma Mba and Harambee Africa for all their promotional efforts, especially Akoma Mba’s recent participation in YAFE 2020.

MK: Children literature is generally marginalized in Africa, when compared to classic literature. Do you agree with this?

NM: That is sadly true! And should not be the case! We must understand that children’s literature is the bedrock or better still the ancestor of adult literature. Once we take cognisance of this fact, we will all put our hands on the plough of promoting the book and reading industry at all levels of our societies.

MK: What is your vision of children’s literature in Cameroon?

My vision is that of hope. Despite the present challenges and timidity, I see light at the end of the tunnel. Let those of us already doing something to change things in this domain keep the momentum. We will smile in the end.

Any last word?

Thank you for all that you are doing to promote children’s literature in Africa. I am grateful for this interview as well. On est ensemble !